To address the information gaps and other deficiencies revealed in the Craigslist debate, the USC Center on Communication Leadership and Policy (CCLP) initiated a project to conduct primary, empirically driven research in the area of technology and trafficking. CCLP partnered with the USC Information Sciences Institute, a leader in computer and information sciences and Internet research. The objective was to explore the hypothesis that innovative and advanced methods for online data collection and analytics can help monitor and combat human trafficking activity.

The research focused on the detection of possible cases of sex trafficking on online classified and social networking sites. While expanding the scope to include labor trafficking was considered, researchers assumed the project was laden with difficulties based on the literature review above and the available methods. Simply, advertising for labor trafficking was considered too covert an activity, wherein traffickers would advertise for legitimate-sounding jobs and subsequently engage in “bait and switch” tactics. Thus evaluating these deceptive advertisements for signals of labor trafficking in online classifieds was not considered a viable research question at this juncture.

The evidence gathered for this report suggests that a specific subsection of adult and escort ads on online classified sites such as Backpage have the potential to be covert advertisements for sex trafficking. It was hypothesized that the type of language displayed, while covert, might reveal signals of trafficking, particularly when the characteristics of the trafficking victim are used to attract clientele.

For example, language or images that include youthful characteristics might indicate a potential sex trafficking case involving a minor. Yet from the start, the research plan was faced with a needle-in-a-haystack problem: The challenge was to create techniques to detect the rare signals of sex trafficking while filtering out the vast amount of “noise” from services that do not fall within the definition of severe forms of trafficking under the TVPA.

It is important to note that researchers did not assume that there must be evidence of human trafficking on numerous online classified and social networking sites, whether mainstream sites such as Craigslist, Twitter, or Facebook, or the numerous explicit sites for the commercial sex industry. It is reasonable to assume, however, that based on the reports and cases cited above, all of these sites have the potential to be used to facilitate trafficking.

Based on existing research and the capabilities of available technologies and methods, the following research questions emerged: To what extent can content on publicly available social networking and online classified sites indicate sex trafficking of adults or children (under the age of 18)? To what extent can keywords be used to detect sex trafficking? Can a spatio-temporal analysis of an event serve as a significant indicator of patterns of sex trafficking activity and behaviors online? Can the location or identity of either traffickers or victims be discerned and mapped?

The Super Bowl as a Potential Event for Trafficking Online

The first study conducted for this report involved a spatio-temporal analysis of online classified ads surrounding an event. An event occurring in one location at a certain time is useful to measure any differences or changes in online behaviors before, during, or after the event. This analysis can be conducted by collecting data around a predetermined event with the hypothesis that researchers might observe an increase or decrease of existing behavior or new patterns based on a search category or topics.

The Super Bowl was chosen as the event for analysis, based on literature indicating a link between major sporting events and trafficking, which suggests that a spike in sex trafficking occurs in host cities during these large events.1 Traffickers reportedly increase their profits by transporting child victims to cities for commercial sexual exploitation during major sporting events and conventions.

In anticipation of the 2012 Summer Olympic Games, the London Councils sought to better understand the impact of mega-sporting events on trafficking in persons. The results of the study were mixed. On the one hand, the Internet is described as possibly playing a role during such events by recruiting girls for prostitution. At the 2010 Winter Olympic Games in Canada, for example, recruiting methods “took place in the schoolyard, over Facebook, Twitter and other social networking sites.”2 On the other hand, the study did not find enough evidence to predict an increase in trafficking around the upcoming Olympic Games.

A number of reports have described a noticeable increase in trafficking during past Super Bowl games. For example, during the 2009 Super Bowl, in Tampa, Florida, the Department of Children and Families took in 24 children trafficked to the city for sex.3 Internet classified ads featuring child victims of prostitution rose sharply in February 2009 in advance of the Super Bowl.4

According to Deena Graves, executive director of child advocacy group Traffick911, law-enforcement officials and advocacy groups rescued approximately 50 girls during the previous two Super Bowls.5 Time reported that during Super Bowl XLIV in Miami, one man was arrested after posting an ad featuring a 14-year-old on Craigslist as a “Super Bowl special.”6

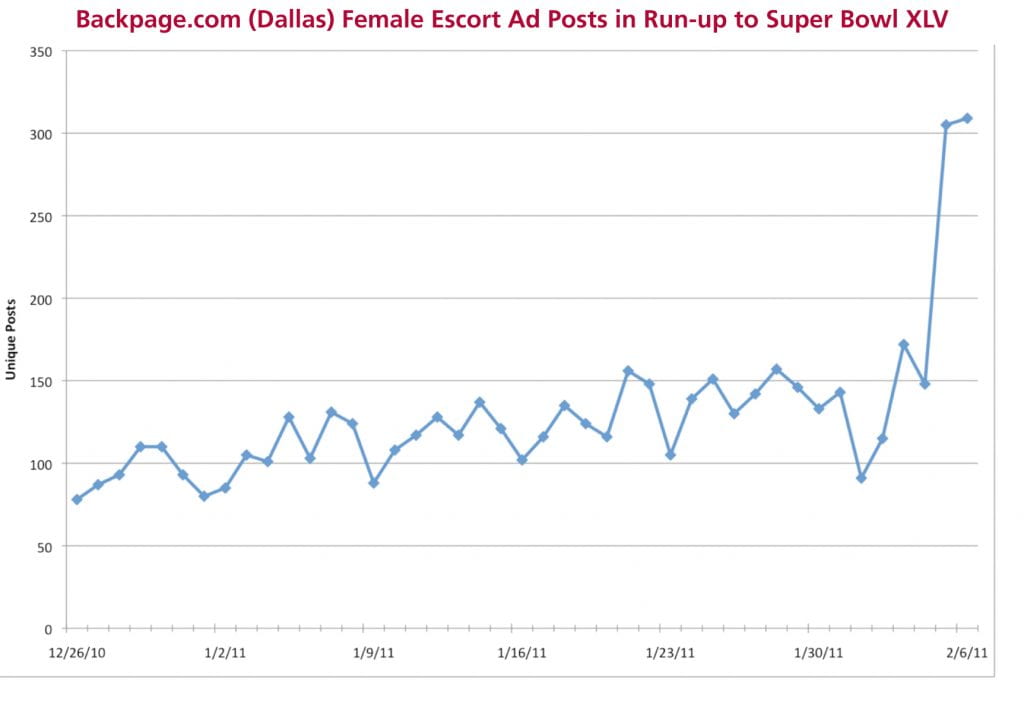

Super Bowl XLV, held on February 6, 2011, in Dallas, presented an opportunity to conduct new analysis on this subject. In anticipation of the event, Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott described the Super Bowl as “one of the biggest human trafficking events in the United States.”7 The Backpage site for the Dallas area was selected as the online classified site where posts would be collected. All posts made to the Adult section of Backpage for the Dallas area were targeted. However, the posts to the Female Escorts section, located within the Adult section of the site, were of primary concern.8 The goal was to measure the frequency of unique posts for a week leading up to Super Bowl Sunday and capture the text within each post. The data collection (shown on the graph below) covered the period from December 27, 2010, to February 6, 2011, and included approximately 5,500 ads. Older posts were gathered to calibrate statistics for historical averages of posts to the section.

The study revealed a noticeable spike in the number of unique posts per day on February 5 and 6.9 More than 300 escort ads were posted on each of these two days, compared to the overall average of 129 posts per day during the period surveyed. While these were unique posts, it is of note that Backpage allows ads to be deleted and reposted, which complicates tracking the actual number of new posts. As a result, the numbers reported should be read as a lower bound on the actual number of posts.

Posts appeared to follow a cyclic pattern, whereby fewer posts appear early in the week and more posts appear on Friday. The smallest numbers of posts typically appear on Sundays, but the graph demonstrates the inverse was the case for February 6, 2011—Super Bowl Sunday. Compared to the average number of posts to the Adult section, the number of posts on Super Bowl Sunday represents an approximate 136% increase.

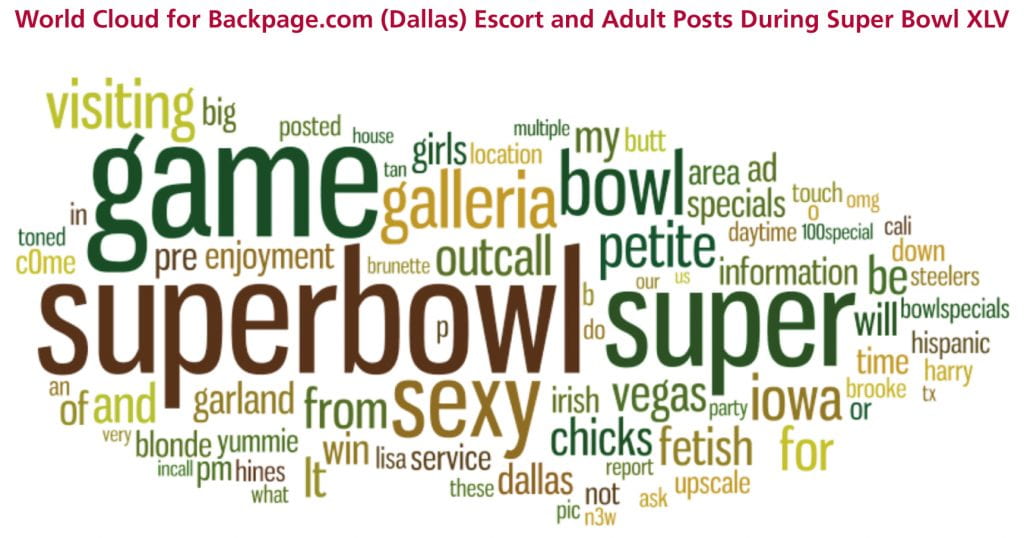

Researchers conducted a content analysis of the ads searched. The word cloud below represents the most salient words extracted from posts on Super Bowl Sunday.

The bigger a word appears, the more salient the term is as measured using standard natural language processing techniques, e.g., term-frequency analysis. As the image shows, the most salient words are mostly related to the Super Bowl and various “specials” that were offered. Other keywords of interest that emerged include “visiting,” “iowa,” “vegas,” and “cali,” which suggest that escorts might have traveled to Dallas (or were transported) across state lines specifically for the Super Bowl.

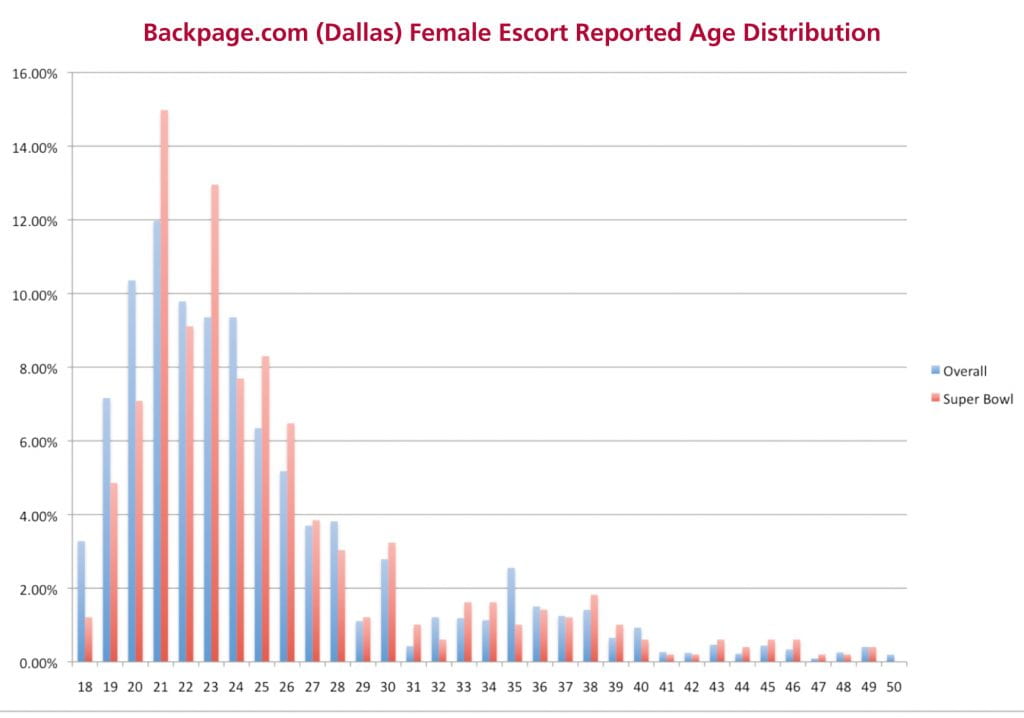

Researchers also analyzed posts for any mention of the age of individuals depicted in the posts. The reported ages were extracted and plotted in the distribution graph below. In analyzing any difference in the age distribution during the Super Bowl weekend compared to the average distribution, it seems that the Super Bowl attracted a slightly older pool of reported ages than usual. Yet these ages are self-reported, which makes it difficult to determine the accuracy of the extracted ages.

It became clear that, when further isolating posts of interest, because of the limited ways to verify the facts within each post, a positive detection of trafficking in persons could not be achieved solely through analyzing the collected texts or images. While isolating the subset of posts indicated possible reasons for further investigation, researchers could not discern signals of sex trafficking of minors or adults with any degree of confidence based solely on the methods used in this study.

Twitter as a Potential Platform for Detecting Trafficking

In order to study a social networking site as a potential platform for detecting trafficking, the next research study involved an analysis of Twitter, which allows users to send short 140-character messages to potentially large audiences in real time. Based on evidence indicating that adult and escort services have been used to advertise for sex trafficking, CCLP and ISI researchers initiated a search of public Twitter feeds for the keyword “escort.” While searching for all Twitter posts containing the word “escort” would capture posts that include services and sex work that do not fall under the legal definition of trafficking, the working hypothesis was that a specific subset of these posts had the potential to be covert advertising for sex trafficking.

Using the Twitter search function, Twitter posts containing the word “escort” were collected for a one-week period in June 2011. The initial search captured 681 posts containing the word “escort.”10 Textual analysis of the posts indicated a significant degree of noise resulting from the multiple meanings of the word “escort” (i.e., a classic problem of polysemy).

Thus, specific linguistic uses were removed from the corpus of collected data (e.g., verb uses such as “escort to the door,” uses with noun modifiers such as “police escort,” and proper nouns such as “Ford Escort”). The result was a smaller pool of approximately 315 posts containing the keyword “escort” that mentioned or advertised adult escort services.

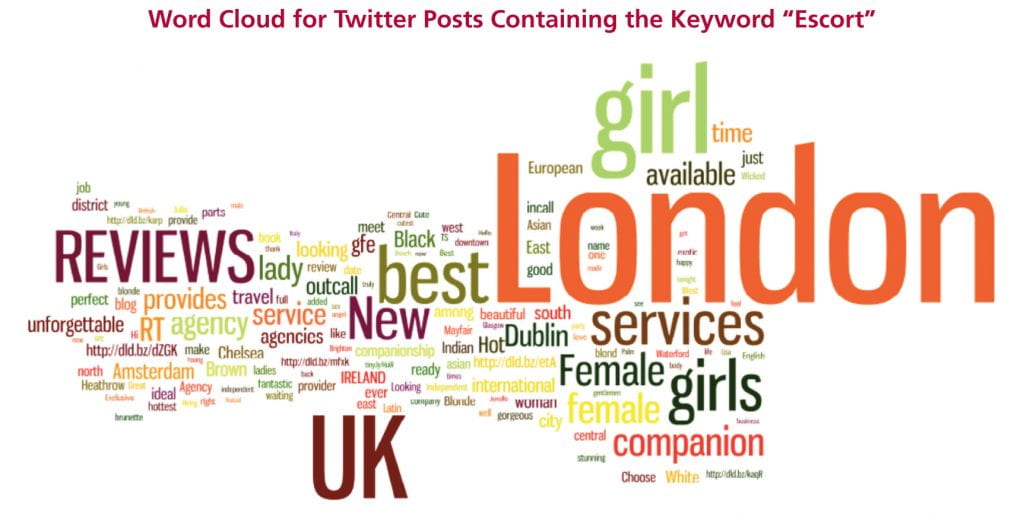

Researchers conducted a term-frequency analysis on the reduced set of Twitter posts, which was used to generate a data visualization word cloud. Since “escort” would obviously appear with the highest word frequency, the word was removed from the collected text in order to highlight other salient words. Based on the word cloud below, one can observe an international component to Twitter escort advertising. For example, the cloud includes postings about escorts from Dublin and Amsterdam, and terms describing nationality and ethnicity such as “Indian” and “Black.” “London” and “UK” were the most frequent terms, primarily because the same London escort service would repeatedly post updates from its Twitter account. Most of the Twitter posts contained links to websites, which upon inspection contained detailed information on the physical characteristics and reported ages of the female escorts, including information on nationality and country of origin. Other terms suggesting age appear in the frequency analysis, such as “girl,” “young,” and “tiny.” The self-reported ages appearing on the websites were 18 and over.

The results of both the Super Bowl and Twitter studies suggest that online data collection, basic computational linguistics, and data visualization can be useful for narrowing the pool of cases, which may warrant further investigation into potential sex trafficking advertisements. More sophisticated methods and tools could be employed to further reduce the pool of potential cases. However, one cannot assume that online tools and methods alone could detect sex trafficking cases with certainty. Researchers hypothesized that if traffickers are using covert, deceptive, and nuanced language to advertise trafficking victims online, this behavior is to a degree that necessitates a human expert to be included as part of a feedback loop. A combination of computer-assisted analysis and data collection with a human expert making informed decisions regarding that data could increase the likelihood of detecting possible cases of human trafficking online.

Integrating Human Experts and Computer-Assisted Technologies

Researchers initiated a third study to detect evidence of trafficking online, incorporating the lessons learned above. The study remained guided by the assumption that a subset of posts from adult and escort classified ads might contain keywords signaling potential cases of trafficking. It was clear, however, that search methodologies were useful only to a point and that a human expert was needed to make an informed decision regarding whether an online classified ad might be a case of trafficking. The following research question emerged: Could online trafficking be detected through a combination of advanced computer-assisted data gathering and analysis techniques and input from an expert human actor?

Researchers decided to generate a data corpus containing a large amount of collected data, which would outpace an individual investigator’s ability to analyze without machine assistance, due to the rate of comprehension and quantity of data. Only with the increased bandwidth of computer processing could a human sort through the collected data for possible cases of interest. Yet the limitations observed in the first two studies suggested the need to develop more advanced methodologies. While computer-assisted tools could create a pool of potential trafficking cases from a large data corpus, researchers hypothesized that including a human expert in the process could (1) increase the possibility of detecting trafficking online and (2) send the computer feedback regarding which posts have greater potential to be trafficking cases, thus allowing the computer to learn through basic artificial-intelligence techniques and algorithms.

A series of questions arose from planning, designing, and implementing this study: Is the purpose of the data collection clear? Who would have access to the data? How would technology ultimately serve the victims of trafficking? Could the technology do harm?

Identifying experts who are adept at handling sensitive information was a key consideration. Special agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation with expertise in crimes against children and human trafficking were asked to provide feedback on the data collected.

Researchers developed a computer prototype to locate and extract or “scrape” the information appearing on the websites, then collect and store the aggregate data for analysis. Sites of interest were identified by the FBI and included for monitoring. A number of online classified and social networking sites were targeted, such as Backpage sites in dozens of U.S. cities and a number of explicit websites and forums known for trafficking activity. Information scraped from the sites includes all text, dates, and photographs.

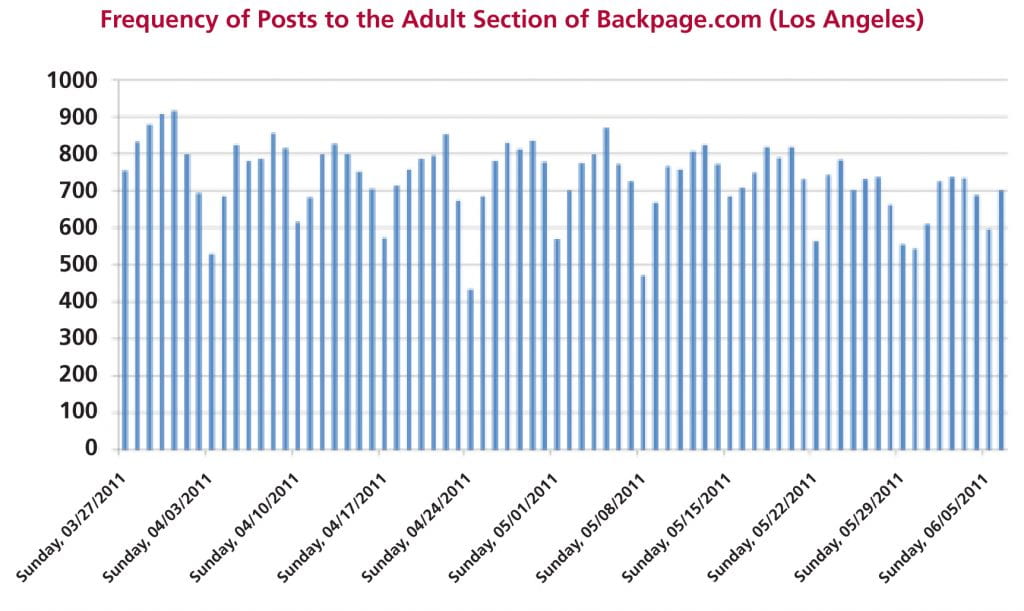

The need for computer assistance can be demonstrated by observing the frequency of the advertisements from the Los Angeles Backpage Adult section in the graph below.

For a period of more than three months, the average number of posts was 735 per day. Taking one week as a sample, from April 24, 2011 to April 30, 2011, approximately 5,150 ads were posted and collected. Those posts contained 392,567 words in addition to tens of thousands of images. Reading at a pace of 200 words per minute,11 it would take an individual approximately 32 hours of continuous reading to review all the language in the posts for the week for Los Angeles Backpage, let alone the dozens of other sites being crawled in this study.12

During the period selected above, about 55,000 posts were collected on the Los Angeles Backpage site.13 Term frequencies included possible age indicators such as “girl” (14,749 mentions) and “young” (145); ethnicities such as “asian” (9,167) and “latina” (5,931); nationalities such as “european” (176) and “thailand” (29); and transitory indicators such as “visiting” (2,366). Researchers then can calculate various permutations of these categories and isolate possible cases.

These basic data mining techniques could allow investigators to respond to potential trafficking cases more quickly, particularly if traffickers advertise in an area for only a short time before moving victims to another location.

Automated data collection, therefore, is a key first step. For an individual sitting at a desk, manually clicking through online classified ads in search of ads that appear to feature underage sex trafficking victims and flagging those ads for analysis is a labor-intensive activity. As Ernie Allen, president and CEO of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children observed, “Web crawling tools may automate this review, by flagging keywords suggestive of child trafficking.” 14 As the size of the data set increases, it approaches limits that exceed the human capacity to comprehend, thus making automated data collection, filtering, flagging, aggregating, and storing via computer processing a necessity. Automating the search thus narrows the pool of online classified ads and conserves the investigator’s manpower for filtering through the posts more efficiently.

Natural language processing is another essential component of this prototype design and implementation. Under the leadership of Dr. Eduard Hovy at the ISI Natural Language Group,15 a number of computational linguistic and machine-learning methods are being explored using the corpus of extracted data. The expert feedback from federal law enforcement agents is a key element, providing evaluative information that can be used to develop algorithms designed to detect possible human trafficking cases.

Facial recognition is being developed for tracking subjects across multiple sites in multiple cities or matching photos of specified criteria among the thousands of photos collected by the prototype. Developing technologies that might determine the ages of subjects based on the photograph alone remains a major technological challenge. Moreover, the issue of false positives and the security of photos of potential trafficking victims are sensitive issues associated with this technology, and they require careful consideration.

Mapping technologies and methods are being employed, as location-based information is extracted from the data collected for this study in an attempt to map the location of individuals mentioned in the posts. While the exact location is often cloaked or not given, researchers are utilizing methods for geo-location. Mapping software could help law enforcement, anti-trafficking organizations, and service providers monitor and track victims and survivors over geographic space. Yet data access and security are primary concerns, as information leading to the location of potential victims could expose those victims to greater harm.

This project is ongoing and the tools and methods are being developed, evaluated, and refined as of the publication of this report.

One issue both researchers and law enforcement face is the challenge of securing techniques and methods in order to remain a step ahead of the covert and malicious activities of traffickers operating in the online space. As the project moves forward, the ultimate goal of this technological intervention, and proof of concept, is to provide real-time data for those who are qualified to act on that information in order to assist a potential trafficking victim or to prosecute a potential trafficker. Sharing methods and tools for analysis of online advertisements with other researchers working in this area is a necessary and proactive next step.16

Notes

- For more information, see Benjamin Perrin, Faster, Higher, Stronger: Preventing Human Trafficking in the 2010 Olympics, The Future Group, November 1, 2007, and Bowen & Shannon Frontline Consulting, Human Trafficking, Sex Work Safety and the 2010 Games: Assessments and recommendations, Sex Industry Worker Safety Action Group, June 10, 2009.

^ - GLE Group, The 2012 Games and Human Trafficking, London Councils, January 2011, 18. ^

- Michelle Goldberg, “The Super Bowl of Sex Trafficking,” Newsweek, January 30, 2011, http://www.newsweek.com/2011/01/30/the-super-bowl-of-sex-trafficking.html. ^

- U.S. Department of Justice, Project Safe Childhood, The National Strategy for Child Exploitation Prevention and Interdiction, August 2010, 33. ^

- Reuters, “Super Bowl a magnet for under-age sex trade,” MSNBC, January 31, 2011, http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/41360579/ns/us_news-crime_and_courts/. ^

- Amy Sullivan, “Cracking Down on the Super Bowl Sex Trade,” TIME, February 6, 2011, http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,2046568,00.html. ^

- Reuters, “Super Bowl a magnet for under-age sex trade,” MSNBC, January 31, 2011, http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/41360579/ns/us_news-crime_and_courts/. ^

- These websites are located on Backpage.com, “Dallas Adult Entertainment,” http://dallas.backpage.com/adult/ and “Dallas Female Escorts,” http://dallas.backpage.com/FemaleEscorts/, last accessed July 6, 2011. ^

- This analysis was conducted by Dr. Don Metzler, Information Sciences Institute, University of Southern California. ^

- The use of the Twitter web-based search function was intended to simulate the results for common users searching for the term “escort.” The resulting number should be considered the lower bound, i.e., lower than the actual number, since the search functionality removes spam, removes duplicates, and personalizes results in some way via a search algorithm. For more information, see “The Engineering Behind Twitter’s New Search Experience,” Twitter Engineering, May 31, 2011, http://engineering.twitter.com/2011/05/engineering-behind-twitters-new-search.html. ^

- An average of 200 words per minute is considered a “reasonable” rate, yet reading words on a screen may slow reading ability to an average of approximately 180 words per minute. Martina Ziefle, “Effects of display resolution on visual performance,” Human Factors 40, no. 4 (December 1998): 555-568. ^

- Of course, an experienced investigator need not read though every word of the vast majority of posts and can use simple keyword searches to narrow the pool. ^

- This analysis was conducted by Hao Wang, Information Sciences Institute, University of Southern California. ^

- Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking: Hearings on H.R. 5575, Before the Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security, 111th Cong. 146 (2010) (statement of Ernie Allen, president and CEO National Center for Missing & Exploited Children). ^

- Other team members include Dr. Don Metzler and Congxing Cai. For more information on The Natural Language Group at the USC Information Sciences Institute, visit http://nlg.isi.edu. ^

- A report prepared by the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory for the U.S. Department of Energy suggests that research is underway on tracking, facial recognition, and data visualization with regard to domestic minor sex trafficking. S.J. Kreyling, C.L. West, and J.R. Olson, Technology and Research Requirements for Combating Human Trafficking: Enhancing Communication, Analysis, Reporting, and Information Sharing, U.S. Department of Energy, March 2011. ^